One of the most important gear decisions I have to make when I'm on the road is what to read. That's especially true when it's a long trip and even more so when weight comes into play. On my trips to Africa to research Heart of Diamonds, I adopted a three-step approach to this important decision.

First was what to read on the flights from New York. My criteria were simple: it had to be paperback mass market fiction that I could enjoyably read off and on for 24 hours, then leave somewhere like an airport waiting room for someone else to enjoy when I was finished. A James Patterson thriller is almost always perfect.

For the return flight, I counted on buying something equally pleasurable somewhere along the way. With luck, I'd find an author published overseas that I wouldn't normally read at home. When I finished it, I donated it to my local library for their fund-raising book sale.

In-country was tougher. I typically read two or three books a week at home, but I sure didn't want to carry a half dozen tomes around the bush. The solution was Shakespeare. I bought a paperback edition of four tragedies, MacBeth, Hamlet, Lear, and Othello. It was a great choice because I could read and re-read them and find something new every time.

Besides, "A drum! A drum! MacBeth doth come!" provided excellent escape from a day filled with the wonders of Africa.

Dave Donelson, author of Heart of Diamonds a romantic thriller about blood diamonds in the Congo

Monday, March 31, 2008

Travel Reading Strategy

Saturday, March 29, 2008

Toe Jam Juice

What's the first thing you're told when visiting a new country? Don't drink the water! Good advice, but sometimes you get lost in the moment. I forgot that basic tenet of travel during a walk through a village near Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable Forest. But at least I lived to tell the tale.

We were visiting a local beverage maker—what we would call a moonshiner in Missouri where I grew up. She said the process begins by making banana juice in a big hollowed-out tree trunk laid on its side like a canoe. The juice maker takes off his shoes and walks on the bananas like someone stomping grapes for wine.

We were visiting a local beverage maker—what we would call a moonshiner in Missouri where I grew up. She said the process begins by making banana juice in a big hollowed-out tree trunk laid on its side like a canoe. The juice maker takes off his shoes and walks on the bananas like someone stomping grapes for wine.

The juice can be drunk as is, but most of it is poured into leaf-lined pits and allowed to ferment for a few days. The resulting banana wine is quite popular. The really good stuff, though, is the banana gin, which is made by distilling the wine in wood-fired stills made from 55-gallon drums and copper tubing. Some technology just can’t be improved.

After the short lecture, our hostess grandly offered samples of all three beverages. I’m a teetotaler, so I stuck with the banana juice, which was quite flavorful. A couple of my friends tried the stronger concoction and pronounced it delicious.

Quite honestly, it wasn’t until I was telling the tale later that I realized how we had broken the first rule of travel: drink only bottled beverages! I guess the banana-stomper responsible for my glass must have had very clean feet.

Dave Donelson, author of Heart of Diamonds a romantic thriller about blood diamonds in the Congo

Sunday, March 23, 2008

Victoria Falls Through Livingstone's Eyes

“You can walk in that direction for 200 kilometers and not see another human being,” said Simon Wilde, pointing north into Zambia from the Zambezi River. The former safari guide was telling me about the countryside where David Livingstone first saw Victoria Falls in 1855, and how little it has changed since. The wide Zambezi is laced with rapids and dotted with islands big and small. It is home to crocodiles, surprisingly aggressive hippos, vicious tiger fish, and hundreds of flamboyant birds, not to mention native fishermen who still ply the mighty stream in makoros, dugout canoes identical to those their ancestors used. In the villages that dot the riverbanks, men still purchase brides for three cows and a little cash and build their homes with mopane poles, mud from termite mounds, and thatch roofs. Political boundaries exist now, but otherwise it hasn’t changed much since Livingstone made his journey more than 150 years ago.

The wide Zambezi is laced with rapids and dotted with islands big and small. It is home to crocodiles, surprisingly aggressive hippos, vicious tiger fish, and hundreds of flamboyant birds, not to mention native fishermen who still ply the mighty stream in makoros, dugout canoes identical to those their ancestors used. In the villages that dot the riverbanks, men still purchase brides for three cows and a little cash and build their homes with mopane poles, mud from termite mounds, and thatch roofs. Political boundaries exist now, but otherwise it hasn’t changed much since Livingstone made his journey more than 150 years ago.

November is barely the beginning of the rainy season in Zambia, so temperatures can reach 40 degrees Celsius (104 F) and the river is still low following the dry months of September and October. Livingstone first came at that time of year, so he and his party paddled through a sluggish four kph current on the Zambezi and navigated around heavy turbulence and exposed rocks in the rapids over the 117 kilometers (72 miles) of the journey.

Dave Donelson, author of Heart of Diamonds a romantic thriller about blood diamonds in the Congo

Thursday, March 20, 2008

My First Plane Flight

Travel is an affliction of mine--one I’ve been fortunate to be able to indulge one way or another for many years now. As a TV executive, a journalist, a consultant, and many times as just a tourist, I’ve visited 48 of the 50 states, and five of the seven continents--so far. I really indulged myself with two trips to Africa researching my novel Heart of Diamonds. I still literally keep an overnight bag packed and ready to go just in case the opportunity arises.

I remember the first time I got on a jet plane. I was a junior in high school and had won a speech contest--the VFW’s Voice of Democracy--for the state of Missouri. That won me a $500 savings bond and a trip to Washington, DC to compete in the national tournament (which I didn’t win). Believe me, my friends, that was heady stuff for a 15-year-old who had never been further away from home than Topeka. I was traveling on my own, too, since my parents couldn't afford to come along and the organization only paid for one plane ticket.

I still have the pictures (somewhere) I took from the tiny window of that 707. If you’re an old folkie, you may remember the Boeing 707 as the plane Gordon Lightfoot sang about in "Early Morning Rain" and Peter, Paul, and Mary in "Leaving on a Jet Plane." In addition to pictures of the monuments and sites I saw, I have one of me shaking hands with Lyndon Johnson, who was President at the time and hadn’t yet announced he wasn’t running for re-election. We stayed in the Shoreham Hotel across the street from another Washington building that made the news a few years later--the Watergate.

I’m starting to sound like Forest Gump, so perhaps its time to bring it to a close.

Dave Donelson, author of Heart of Diamonds a romantic thriller about blood diamonds in the Congo

Tuesday, March 18, 2008

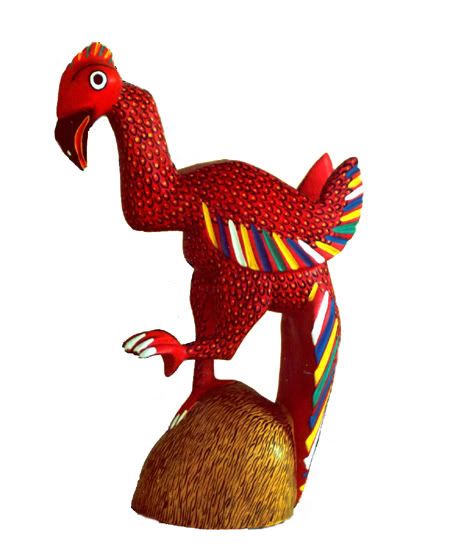

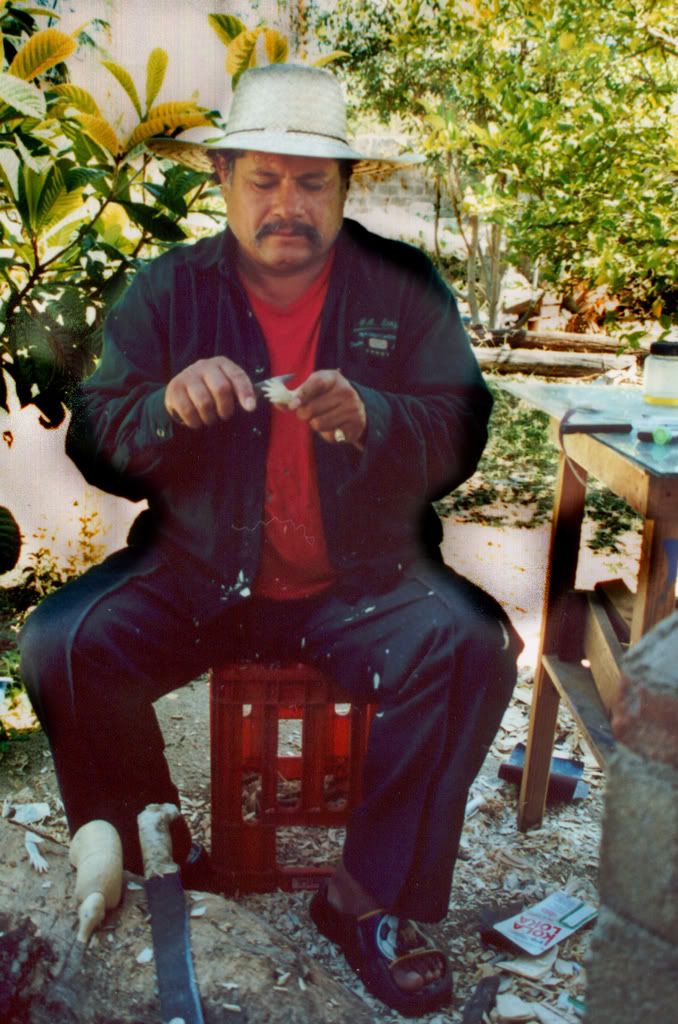

Carved Creatures of Oxaca

Fire-breathing crocodiles and flying giraffes roam folk art museums and shops around the world. They are alebrijes—hand-carved wooden figures from the Mexican state of Oaxaca.

Zapotec and Mixtec Indians have been carving in the region for at least 2500 years. Their intricate bas relief work can be seen in the ruins of Monte Alban, the ancient city sitting on a mountaintop overlooking the valley. Their descendants live in villages specializing in crafts like weaving, pottery, and metalwork as well as woodcarving.

The best-known carvers work in Arrazola, San Martin Tilcajete, and La Union Trejalapan, which are villages a few dusty miles from the city of Oaxaca. In the last thirty years, almost 100 of the approximately 500 families in Arrazola alone have turned from subsistence farming to take up the craft.

Just as on a family farm, everyone has a role in the enterprise. Traditionally, the men carve while the women and older children sand and paint. The younger children recruit customers from among the tourists and collectors drawn by the remarkable array of unique figures, masks, and furniture.

Subjects range from native creatures like armadillos, coyotes, and lizards to barnyard animals and birds. The carvers have responded to customer requests, too, by adding animals never seen in Mexico like polar bears and giraffes. Imaginary creatures—dragons, mermaids, space aliens, and many beyond simple names—compliment the typical carver’s repertoire.

Many carvers produce both real and fanciful human figures as well. Nativities and angels compete for shelf space with drunken devils and reveling skeletons, which are used in village scenes showing Day of the Dead celebrations.

Pieces range from two-inch armadillos to six-foot wooden skeletons. Styles can be primitive and rough or smooth, round, and flowing. Their appeal comes from both the carving and the painting, both accomplished using simple hand tools and finishes. The family workshop is often a shady tree in the backyard. The carver’s “tool box” holds a machete, pocket knife, a few kitchen knives, and maybe a gouge or chisel.

Pieces range from two-inch armadillos to six-foot wooden skeletons. Styles can be primitive and rough or smooth, round, and flowing. Their appeal comes from both the carving and the painting, both accomplished using simple hand tools and finishes. The family workshop is often a shady tree in the backyard. The carver’s “tool box” holds a machete, pocket knife, a few kitchen knives, and maybe a gouge or chisel.

Most of the wood comes from the copal tree, which once grew on the hillsides surrounding the villages. The local trees were victims of the craft industry’s success, though, and have mostly disappeared. The few remaining trees are protected by environmental regulations and stiff fines are levied against poachers. Now copal is purchased from sellers who harvest it from the nearby Sierra Madre mountains.

Copal resembles basswood in density, grain, and workability. The carver, unlike a furniture maker, looks for curving, twisted branches to make pieces like spiral-tailed lizards and sinuous cats. Very little of the tree goes unused. The carver adds features using found materials like goat (or human) hair, cactus spines, splinters of wood, and fibers from maguey leaves.

The figures may be fanciful, but the carving is pretty straightforward. Once the carver visualizes the shape, he roughs it out with a machete. Final form and detailing are done by knife and the piece is left to dry for a day or so in the sun. If the shape of the branch require it, appendages like legs and wings are glued in place. These are also sometimes inserted loose into holes so the buyer can more safely pack and ship them.

The pieces are sanded and a base coat or sealer is applied. Then the painter adds the remarkable patterns that distinguish the genre. Most of them use standard acrylic craft paints, although some of the more traditional apply aniline dyes which penetrate the wood and produce deeper, almost fluorescent, colors but fade over time. Either way, the painters have a bright palette of primary and complementary colors that they use to the fullest.

Brushes are only one of the many applicators used. The painter often chooses a sponge for base-coating because it’s cheaper and more efficient. Thorns of the mescal cactus or sharpened carving scraps make tiny dots, patterns, and other details.

The painting adds a super-normal dimension to the figures. A pointillist rabbit may coat the back of a howling coyote. Tiny strawberries and grapes may decorate an armadillo. Scales the size of the “o” in “dragon” and multi-colored dots the size of the period at the end of this sentence may cover a foot-tall bird. The variety and novelty of decoration show no boundaries.

Making fun figures like these doesn’t require a great deal of technical woodworking knowledge. More important are the qualities of the Oaxacan carver: patience, imagination and the instinct to unite art and craft.

Dave Donelson, author of Heart of Diamonds a romantic thriller about blood diamonds in the Congo

Sunday, March 16, 2008

Building A Mud House

One of the best places I visited in Zambia was the village of Siankaba on the Zambezi River. While there, I got to know “Doctor,” a guide who proudly showed me the new home he was building. Many of the details he explained found their way into my novel, Heart of Diamonds.

In Siankaba, just as where I live in New York, no project begins without a building permit issued by the appropriate authorities. Before Doctor could build his new home, he had to get permission from the village headman since all land belongs to the village. Doctor’s old house, by the way, won’t be sold. It will belong to the next person who needs a home as adjudged by the headman.

Once the site is approved, it is cleared and leveled, then holes where the walls will be are dug about a foot deep and two feet apart. They will hold upright studs of straight mopane logs about four inches thick and perhaps eight feet long. They’re held in the foundation holes with tamped earth, not cement.

They’re held in the foundation holes with tamped earth, not cement.

Headers of similar size longs are lashed to the top of the studs. Thin sticks and reeds are woven through the studs, with holes left for doors and windows. Along with the headers, they provide stiffness to the framework. They also serve as lath to hold the mud which comes next.

The mud is more than just dirt and water. It’s mixed with soil from the gigantic termite mounds that dot the countryside—earth that has passed through the insect’s digestive tract. It contains a hardening agent that enables the mounds to withstand rains and attacks by predators for a hundred years or more. The walls of a well-built hut will be as hard and durable as concrete once they dry in the hot equatorial sun.

Mopane joists are lashed to the wall frame and a roof is laid on top. It may be tin, which lasts 20+ years, or thatch, which is good for seven but costs considerably less. Depending on the financial health of the builder, doors and windows may be nothing more than cloth or canvas draped over the openings or prefab manufactured items with glass and locks.

Dave Donelson, author of Heart of Diamonds a romantic thriller about blood diamonds in the Congo

Midnight Welcome to Entebbe

You may have seen a version of Entebbe International Airport in The Last King of Scotland. The movie captured the feel of the place--it's not exactly brimming with the spirit of welcome.

That was my first impression,too, when Nora (my wife) and I arrived there for the first time, but I was wrong. There were all kinds of friendly things going on, as we found out a few minutes after arrival.

No airport looks very good after you've spent 24 hours getting there--in coach. But Entebbe is sadder looking than most, especially after midnight. At least it was bustling. Our flight was one of a handful of big jets from Europe to stop there every week. Once we deplaned and the next load of passengers boarded, its next stop was Amsterdam, so there was quite a bit of activity. But despite all the hustling porters and hopeful taxi drivers, it was still midnight in Uganda, dark, mysterious, and just a little bit threatening. It was an appropriate setting, I suppose, since I was there to do research for my novel, Heart of Diamonds.

I assumed it was too late to change some dollars for Ugandan shillings, but our driver, a can-do sort of guy, said it would be no problem. We followed him around the terminal away from the dwindling crowd in the dimly-lit parking lot into a dark passageway that led to an even darker staircase. Bad thoughts bubbled to the surface of my jet-lagged brain, but I followed him anyway.

We went up the stairs to a glass storefront that looked very, very closed. The door slid open at our touch, however, and we stepped up to the counter--even though there wasn't a human in sight nor any light to see them by if there had been.

Our driver rapped sharply on the counter and a girl popped her head up from the opposite side, looked around with surprise, then disappeared beneath the counter again.

We heard a little scuffling and a smothered giggle, then the girl appeared again, wearing a sheepish grin this time. Mustering her dignity while trying to button her blouse, she stood up straight and asked how she could be of service. A cough came from beneath the counter, which she answered with a kick.

With love all around, I decided Entebbe wasn't such an unfriendly place after all.

Dave Donelson, author of Heart of Diamonds a romantic thriller about blood diamonds in the Congo

Scotland's Kingsbarns, The Ultimate Buddy Trip

A buddy trip to the ancestral home of the game is mandatory at least once in each golfer’s lifetime. It may take a little more planning than a quick weekend in Florida, but the chance to tee it up where the game was invented makes it all worthwhile. The Old Course at St. Andrews is a must, but just six miles along a winding, craggy road on the Fife coast is Kingsbarns. This may be the best links course ever built—a bold statement, but play it before you disagree with me.

Kingsbarns is a newly constructed track that opened in 2000, although golf was played on the site from 1793 to 1939, when World War II closed it down. Every hole on the course has a view of the ferocious North Sea—and six holes actually skirt it. Like all links golf, you don’t play the course, you play the wind, which can turn 150-yard par-threes into driver holes and enable you to reach a 350-yard par-four with a three-wood. Kingsbarns was the site of the 2006 Dunhill Cup, and many believe it is destined to join the British Open rotation.

Walking is mandatory on Kingsbarns as it is on most courses in the auld sod. That's the way the game should be played anyway and having a well-informed caddy along, especially the first time you play the course, is well worth the price.

We stayed at the St. Andrews Golf Hotel, a small but elegant affair overlooking St. Andrews Bay and an easy five-iron from the R&A Clubhouse. The Dunes Dining Room serves delectable Continental fare and features an extensive wine list.

Dave Donelson, author of Heart of Diamonds a romantic thriller about blood diamonds in the Congo