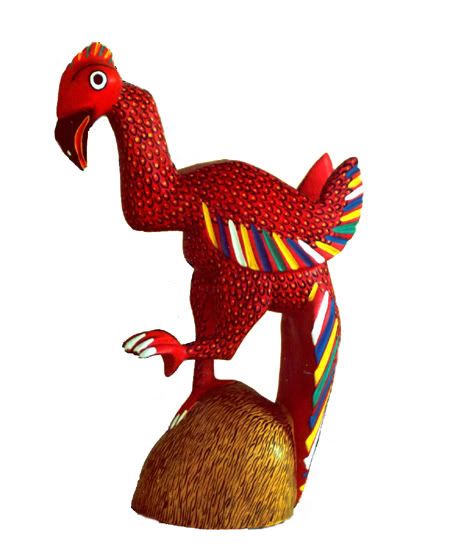

Fire-breathing crocodiles and flying giraffes roam folk art museums and shops around the world. They are alebrijes—hand-carved wooden figures from the Mexican state of Oaxaca.

Zapotec and Mixtec Indians have been carving in the region for at least 2500 years. Their intricate bas relief work can be seen in the ruins of Monte Alban, the ancient city sitting on a mountaintop overlooking the valley. Their descendants live in villages specializing in crafts like weaving, pottery, and metalwork as well as woodcarving.

The best-known carvers work in Arrazola, San Martin Tilcajete, and La Union Trejalapan, which are villages a few dusty miles from the city of Oaxaca. In the last thirty years, almost 100 of the approximately 500 families in Arrazola alone have turned from subsistence farming to take up the craft.

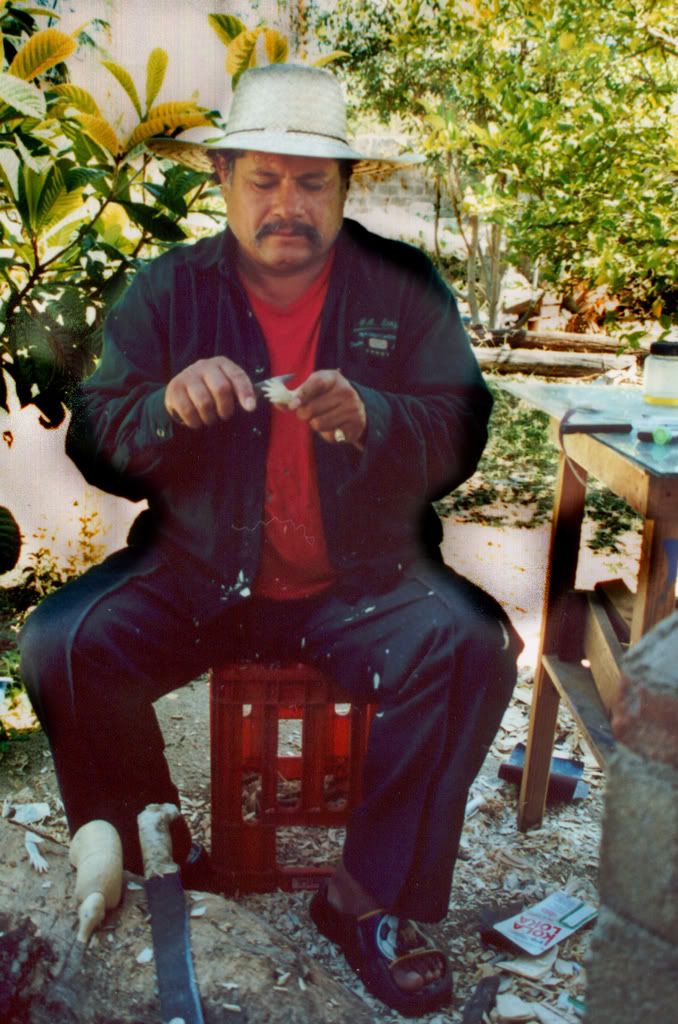

Just as on a family farm, everyone has a role in the enterprise. Traditionally, the men carve while the women and older children sand and paint. The younger children recruit customers from among the tourists and collectors drawn by the remarkable array of unique figures, masks, and furniture.

Subjects range from native creatures like armadillos, coyotes, and lizards to barnyard animals and birds. The carvers have responded to customer requests, too, by adding animals never seen in Mexico like polar bears and giraffes. Imaginary creatures—dragons, mermaids, space aliens, and many beyond simple names—compliment the typical carver’s repertoire.

Many carvers produce both real and fanciful human figures as well. Nativities and angels compete for shelf space with drunken devils and reveling skeletons, which are used in village scenes showing Day of the Dead celebrations.

Pieces range from two-inch armadillos to six-foot wooden skeletons. Styles can be primitive and rough or smooth, round, and flowing. Their appeal comes from both the carving and the painting, both accomplished using simple hand tools and finishes. The family workshop is often a shady tree in the backyard. The carver’s “tool box” holds a machete, pocket knife, a few kitchen knives, and maybe a gouge or chisel.

Pieces range from two-inch armadillos to six-foot wooden skeletons. Styles can be primitive and rough or smooth, round, and flowing. Their appeal comes from both the carving and the painting, both accomplished using simple hand tools and finishes. The family workshop is often a shady tree in the backyard. The carver’s “tool box” holds a machete, pocket knife, a few kitchen knives, and maybe a gouge or chisel.

Most of the wood comes from the copal tree, which once grew on the hillsides surrounding the villages. The local trees were victims of the craft industry’s success, though, and have mostly disappeared. The few remaining trees are protected by environmental regulations and stiff fines are levied against poachers. Now copal is purchased from sellers who harvest it from the nearby Sierra Madre mountains.

Copal resembles basswood in density, grain, and workability. The carver, unlike a furniture maker, looks for curving, twisted branches to make pieces like spiral-tailed lizards and sinuous cats. Very little of the tree goes unused. The carver adds features using found materials like goat (or human) hair, cactus spines, splinters of wood, and fibers from maguey leaves.

The figures may be fanciful, but the carving is pretty straightforward. Once the carver visualizes the shape, he roughs it out with a machete. Final form and detailing are done by knife and the piece is left to dry for a day or so in the sun. If the shape of the branch require it, appendages like legs and wings are glued in place. These are also sometimes inserted loose into holes so the buyer can more safely pack and ship them.

The pieces are sanded and a base coat or sealer is applied. Then the painter adds the remarkable patterns that distinguish the genre. Most of them use standard acrylic craft paints, although some of the more traditional apply aniline dyes which penetrate the wood and produce deeper, almost fluorescent, colors but fade over time. Either way, the painters have a bright palette of primary and complementary colors that they use to the fullest.

Brushes are only one of the many applicators used. The painter often chooses a sponge for base-coating because it’s cheaper and more efficient. Thorns of the mescal cactus or sharpened carving scraps make tiny dots, patterns, and other details.

The painting adds a super-normal dimension to the figures. A pointillist rabbit may coat the back of a howling coyote. Tiny strawberries and grapes may decorate an armadillo. Scales the size of the “o” in “dragon” and multi-colored dots the size of the period at the end of this sentence may cover a foot-tall bird. The variety and novelty of decoration show no boundaries.

Making fun figures like these doesn’t require a great deal of technical woodworking knowledge. More important are the qualities of the Oaxacan carver: patience, imagination and the instinct to unite art and craft.

Dave Donelson, author of Heart of Diamonds a romantic thriller about blood diamonds in the Congo

1 comment:

This is a grate hand made Creatures by wood. I saw your handmade Creatures. They are so cute and charming, i am sure the Creatures in our neighborhood would love it!

Post a Comment